This Spring semester of 2018 has brought me many new and exciting experiences as a member of the Childress Lab. I was fortunate enough to travel to the Keys for my second trip in December and again over spring break. I found that with each trip my growing knowledge about marine organisms and marine systems allowed for a new euphoria of understanding. The courses I've taken this semester and the training I've received in the Childress Lab are preparing me for field research in a way I never imagined. However, this semester I've also been exposed to a side of scientific academia for the first time. Morgan and I had the opportunity to present a poster on The Impacts of Hurricane Irma on The Middle Florida Keys at several academic symposiums. Going through the poster making process prepared us for many of the steps involved in publishing scientific literature and allowed us to share our wonderful research with members of the Clemson community. Every member of the CMR team was also charged with the task of designing a project for this summer as well as writing and presenting the proposal. I throughly enjoyed this assignment and took the opportunity to design a project with methods that could easily be worked into the standard data collection methods we utilize. This proposal focuses on how reef fish utilize ledges, an excellent bridge between Kara's work studying the relationship between structure and fish community and the results we found examining the impact of hurricane Irma. As the semester concludes I am eager to return to the keys, this time for eight weeks, and excited about what I still have to learn not only in the field but as a member of the CMR team for many semesters to come.

This Spring semester of 2018 has brought me many new and exciting experiences as a member of the Childress Lab. I was fortunate enough to travel to the Keys for my second trip in December and again over spring break. I found that with each trip my growing knowledge about marine organisms and marine systems allowed for a new euphoria of understanding. The courses I've taken this semester and the training I've received in the Childress Lab are preparing me for field research in a way I never imagined. However, this semester I've also been exposed to a side of scientific academia for the first time. Morgan and I had the opportunity to present a poster on The Impacts of Hurricane Irma on The Middle Florida Keys at several academic symposiums. Going through the poster making process prepared us for many of the steps involved in publishing scientific literature and allowed us to share our wonderful research with members of the Clemson community. Every member of the CMR team was also charged with the task of designing a project for this summer as well as writing and presenting the proposal. I throughly enjoyed this assignment and took the opportunity to design a project with methods that could easily be worked into the standard data collection methods we utilize. This proposal focuses on how reef fish utilize ledges, an excellent bridge between Kara's work studying the relationship between structure and fish community and the results we found examining the impact of hurricane Irma. As the semester concludes I am eager to return to the keys, this time for eight weeks, and excited about what I still have to learn not only in the field but as a member of the CMR team for many semesters to come.

Monday, April 30, 2018

This Spring semester of 2018 has brought me many new and exciting experiences as a member of the Childress Lab. I was fortunate enough to travel to the Keys for my second trip in December and again over spring break. I found that with each trip my growing knowledge about marine organisms and marine systems allowed for a new euphoria of understanding. The courses I've taken this semester and the training I've received in the Childress Lab are preparing me for field research in a way I never imagined. However, this semester I've also been exposed to a side of scientific academia for the first time. Morgan and I had the opportunity to present a poster on The Impacts of Hurricane Irma on The Middle Florida Keys at several academic symposiums. Going through the poster making process prepared us for many of the steps involved in publishing scientific literature and allowed us to share our wonderful research with members of the Clemson community. Every member of the CMR team was also charged with the task of designing a project for this summer as well as writing and presenting the proposal. I throughly enjoyed this assignment and took the opportunity to design a project with methods that could easily be worked into the standard data collection methods we utilize. This proposal focuses on how reef fish utilize ledges, an excellent bridge between Kara's work studying the relationship between structure and fish community and the results we found examining the impact of hurricane Irma. As the semester concludes I am eager to return to the keys, this time for eight weeks, and excited about what I still have to learn not only in the field but as a member of the CMR team for many semesters to come.

This Spring semester of 2018 has brought me many new and exciting experiences as a member of the Childress Lab. I was fortunate enough to travel to the Keys for my second trip in December and again over spring break. I found that with each trip my growing knowledge about marine organisms and marine systems allowed for a new euphoria of understanding. The courses I've taken this semester and the training I've received in the Childress Lab are preparing me for field research in a way I never imagined. However, this semester I've also been exposed to a side of scientific academia for the first time. Morgan and I had the opportunity to present a poster on The Impacts of Hurricane Irma on The Middle Florida Keys at several academic symposiums. Going through the poster making process prepared us for many of the steps involved in publishing scientific literature and allowed us to share our wonderful research with members of the Clemson community. Every member of the CMR team was also charged with the task of designing a project for this summer as well as writing and presenting the proposal. I throughly enjoyed this assignment and took the opportunity to design a project with methods that could easily be worked into the standard data collection methods we utilize. This proposal focuses on how reef fish utilize ledges, an excellent bridge between Kara's work studying the relationship between structure and fish community and the results we found examining the impact of hurricane Irma. As the semester concludes I am eager to return to the keys, this time for eight weeks, and excited about what I still have to learn not only in the field but as a member of the CMR team for many semesters to come.

Thursday, April 26, 2018

Ride the Tide

Last summer I had the opportunity to conduct conservation research with the Sea Turtle Conservation Project at Hunting Island State Park. I grew up volunteering with conservationists on the sea islands of coastal South Carolina and witnessed first-hand the destructive power of nature, poor resource management, and habitat fragmentation. Hunting Island, South Carolina is a sub-tropical barrier sea island that harbors a 3.2 km saltwater lagoon and an ocean inlet – both critical shorebird habitats and home to hundreds of species of wildlife, including approximately 15,000 sea turtle visitors, annually. Lucky me; it’s in my backyard.

In conjunction with citizen scientists from Friends of Hunting Island (FOHI), we identified and monitored active nest sites of several species of threatened or endangered sea turtles. I learned to distinguish between green turtle (Chelonia mydas), diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin), and loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) tracks and nesting sites throughout the season (May-September). Occasionally a turtle would lay her clutch too low on the beach and we would have to move it to a safer location, above the high tide water line. Because turtle sex is temperature dependent, we meticulously excavated these nests using egg cartons so that each of the 100-120 eggs and their exact placement could be accurately mapped to avoid altering the naturally occurring sex ratio. Finally, we planted wire mesh around each nest site to prevent predation from scavengers or accidental destruction from human visitors during the fragile 70-day gestation period. All we could do then was monitor and educate park visitors – and hope.

One evening, I was invited to spend the night monitoring the beach for crawls (new nests). Around 3AM, I stumbled across a fresh set of tracks and quietly followed them up the beach towards a dune. As it turned out, it made little difference. The nesting mother had created a veritable sandstorm from her noisy digging and impeded my approach. I turned my headlamp setting to its red setting to avoid alarming her, and when she rested briefly, it quickly became obvious that she was entranced in egg-laying. I observed quietly, counting each egg, until she began burying them. After an hour she finally began the long haul back to the ocean. Watching her descend back into the black waters, I wondered at the event I had just witnessed.

Witnessing a nesting event is special, but I had not expected to be present for a hatching. Early one morning, finally came the call over the radio that our first nest was hatching. Rangers, interns, and FOHI citizen scientists piled into the UTVs and sped through the pre-dawn to the nesting site on North beach. The sand was roiling, a sure sign that the hatchlings would emerge at any moment. Waiting without interfering was one of the most challenging moments of my life. Finally, tiny loggerhead sea turtles began appearing, clumsily climbing from the nest. As we flanked the dune to guide the hatchlings towards the ocean, the feeling of solidarity was indescribable.

Once the hatchlings made it safely into the water, we began excavating the nest for DNA samples. As a barrier island, Hunting Island incurs a vast amount of erosion each year from storm surges, flooding, and hurricanes. One of the primary conservation concerns was that young mothers might not be able to locate proper nesting sites due to habitat degradation. Thus, we salvaged egg shells from the hatched nest to genetically identify individuals, perhaps trace sea turtle lineages, and collect data that could help determine rates of nesting site fidelity. The thought of positively impacting these fragile populations is reason for hope.

Returning to Clemson last fall, I was determined to branch out and find other like-minded marine conservationists. I found that refuge in Dr. Childress' behavior lab and in Conservation of Marine Resources. It was here that I began to understand how to manipulate acoustic telemetry data, how to analyze communities from reef surveys, and how to synthesize and present research to a variety of audiences. Throughout the semester, we struggled and debated and crunched our way through massive data files, but in the end, working with other passionate conservationists was a pure pleasure.

Wednesday, April 25, 2018

Finding My Niche While Sharing My Passion

Global conservation

efforts will not make a significant impact until the general public is engaged

and aware of how each individual’s actions can influence the health of our

planet. After I graduate, I intend to dedicate my life’s work to

investigating the effects of and solutions to climate change as well as

communicating climate and ecological science to the public in a way that

promotes both understanding as well as a desire to become engaged in the

process. For this to be truly effective, it must occur from a global political

level to a personal and individual level.

Creating E-learning modules allows me to leverage my passion

for public engagement in a way that will affect positive engagement and

educational impact in science. The opportunity I have had to use my work

experience to help future undergraduate scientists has reinforced and added confidence

to my passion for engaging the public in this urgent and worthwhile endeavor. I need to spend more time learning and

contributing to other’s research before deciding which direction to go with my

own investigative efforts. The task at hand for me right now is to find several

internships that will allow me to contribute to my field while exploring its

various facets in order clarify where I want to find my niche, and I have

little doubt that I will be able to continue using my skills in developing

e-learning modules to engage students and the public wherever my internships

take me.

If you would like to see more of these modules, click on the links below.

Substrate Module: https://360.articulate.com/review/content/fd99efaf-bd0f-4eb9-b280-0422a90cb33f/review

Parrotfish Module: https://360.articulate.com/review/content/2cf19848-bee1-466c-8381-13a4fda0a739/review

Friday, April 20, 2018

Amazing End of Year Presentations from the CMR Team

Click on these links to see some of our team's creative ideas for future research and outreach projects.

Reef Awareness

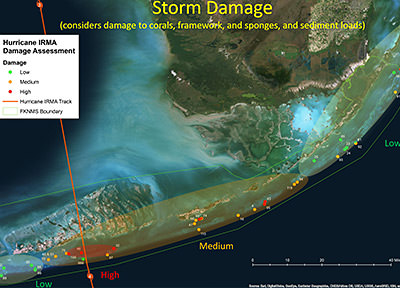

In September 2017, the world saw one of the largest hurricanes ever recorded, decimate the Caribbean and slam full force into the East Coast of the United States. The damage was insurmountable and even today is still being cleaned up as these communities try to recover. One subset of communities drew our lab's particular interest... the coral reefs. Having studied the reefs for years, we had a wealth of data at our hands and the unique opportunity to study this storm damage first hand and compare it to what we know about these reefs already. When I started working in the lab for this CI, my project didn't really have a direction but this storm gave me the chance to focus on the recovery of these reefs as they start to rebuild. Pictured below is an initial assessment of reef damage put out by the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

As you can see, most of the damage is centered closer to the hurricane but it varied across all of the reefs. The worst damage was seen by algae, sponges, and soft corals as the hurricane picked up massive amounts of sand and blasted the reefs with it. Some hard corals were scoured as well as flipped over by the wave energy. The fish communities scattered as their homes were destroyed. These reefs are essential to this ecosystem, as is their recovery, so we plan to continue monitoring these reefs to see how they respond to a natural disaster of this magnitude.

One thing we have been able to do to help is spread awareness. Our lab had the honor of presenting three posters at the Clemson Biological Sciences Annual Student Symposium where we were awarded the best graduate talk and top 3 undergraduate poster. We were able to share our knowledge of these reefs and how important they are to our ecosystem with so many people and we hope to continue spreading awareness. Coral reefs are the rainforests of the sea in both their biodiversity but also in their endangerment. Simple things you can do to help include limiting your use of single use plastic, recycling, conserving energy, and encouraging others to do the same. The sea creatures will appreciate it.

Tuesday, April 17, 2018

A Big Step: A SCUBA Story

"Look straight out, right hand on your mask and reg, left hand on your inflator hose, and give me a big step". These words opened up an entire new dimension to my world. For some reason I have always been fascinated by what is around the next bend, or what is just outside of my reach, and especially what is just beyond what I can see. It is a large part of what keeps me adventuring. This situation was no different. I have grown up fishing my entire life and several times found myself wondering what really went on under the boat, beyond what I could see. This phrase, said by my dive instructor, Kylie, opened up an entire new world where everything, it seems, is just out of sight.

"Look straight out, right hand on your mask and reg, left hand on your inflator hose, and give me a big step". These words opened up an entire new dimension to my world. For some reason I have always been fascinated by what is around the next bend, or what is just outside of my reach, and especially what is just beyond what I can see. It is a large part of what keeps me adventuring. This situation was no different. I have grown up fishing my entire life and several times found myself wondering what really went on under the boat, beyond what I could see. This phrase, said by my dive instructor, Kylie, opened up an entire new world where everything, it seems, is just out of sight.

This past Friday I found myself walking across the parking lot of a community center, scuba tanks in hand, hundreds of miles from where you would think people actually scuba dive. But, as strange as it might seem, even being able to stay underwater in a community swimming pool for 10 minutes is a weird first time experience. It was training day, which meant going through a series of scenarios such as clearing your mask, finding your regulator underwater, and several different types of ascents. The mask clearing was the one thing that made me a little uneasy at first. Being underwater and blind does not sound like my idea of a good time. After all, a hefty purpose for me doing this is to be able to see what I can't on the surface. Mask cleared and sight restored, my dive buddies and I finished up the rest of the exercises quickly and with hardly any issues. We got the all clear from Kylie to go to the lake and experience our first actual dive.

Have you ever drank water so cold that your teeth hurt afterwards? Well we dove in that. At least it felt like it we did. And this time there was no big step off of a boat into the water. It was a slow walk down a boat ramp into, and then underneath, the frigid water. For some reason for me the biggest thrill didn't come from looking down to the lake bottom, which was the expected mud, beer cans, tires, and fishing lures, but came from looking up to the sky from 20 feet below the surface of the water. Maybe it is a grass is always greener on the other side thing, but when I am on the surface I look down and when I'm down I look to the surface. The light from the surface seems to fall like rain through the water, a complete role reversal from what I had previously ever seen. Looking around, I could only see 15 feet or so before it was no longer possible to see beyond a sort of green curtain in the water. This is what really enticed my nature and caused me to immediately fall in love with diving. It makes it seem like there is always something newer or exciting around the next corner. Something just outside of my sight that I have to go see and explore for myself.

The next day we headed back out for the last dive before we would be certified. We boarded a pontoon boat this time and headed just across the lake to the mistakenly named Hot Hole as it was no warmer than the boat ramp we dove the day before. Weighted down with scuba gear I shuffled to the edge of the boat and, with instruction from Kylie, I looked straight out, put my right hand on my mask and reg, left hand on my inflator hose, and took a big step, and after a descent, training excercises, and a celebratory ride of the current made from the release of water from the power plant, I surfaced from a world filled with brand new adventures that are just out of my sight. Now, I simply have to go after them.

Thursday, April 12, 2018

The Fall Break That Changed My Life

This past fall, I received an email from the honors college about a trip during fall break to the Florida Keys where we would be helping to restore the community after Hurricane Irma a couple months earlier. I thought it would be a nice way to spend my fall break, helping the people who were most impacted by this terrible event, but little did I know it would change the course of my college career, and even my future.

When we got there we settled into the Keys Marine Lab where we would be staying for the remainder of the trip. It was a long drive, so we were all pretty tired and we had a lot of work ahead of us. The next day we cleaned up, out, and around the entire tank system, raked, and picked up debris at the marine lab so they could get back to being functional again. It was hard, but impactful work. We had tons of fun too and the group I was with made it a good time doing good things!

In the next few days we got to restore the touch tank, where visitors can see and touch little critters we could find from the nearby ecosystem, and we also went to someones house to help them repaint their walls and catalyze the rebuilding process. What we saw was disheartening (piles upon piles of debris and gas stations fallen over, houses destroyed), but the hope and the optimism the community had was inspiring.

An image of the heaps of debris collected by cleanup efforts

For our day off, we took the boat out and visited some reefs where some members of the team collected data while the rest of us snorkeled and took pictures/video. This was the first time I had done anything that far off shore and the beauty of being in a new place among new animals was eye opening. I loved being a part of their world and beginning to understand their lives at the reef, who the fish interact with and how they interact with the reef. I saw a sea turtle for the first time along with a barracuda (which I didn’t know was a barracuda at the time), and also did my part to pick up some trash I saw. It was nothing short of perfection.

I am now a lab volunteer for the Marine Ecology and Marine Conservation Creative Inquiry and will soon be enrolled this coming fall. If I had not taken this trip and seen first hand the impact that Hurricane Irma had on the Florida Keys community and the reef communities nearby, I don’t know if I would be where I am right now. I got a chance to build relationships with the most amazing role models and leaders that I am proud to be learning from right now. Hopefully, I will make another visit and be able to scuba dive. I also hope to be a part of the data collection process and to learn more about how we can save this wonderful ecosystem.

Gallavanting in the Galápagos

It was long

before I came to Clemson to major in biological sciences that I became interested in

the natural world. I first began learning about Charles Darwin and his findings

on evolution in middle school. Traveling to the site of many of his

observations, the Galápagos Islands, quickly became a life goal of mine. This dream

came true over winter break my sophomore year of high school when family decided to go on an alternative

vacation. After flying into Quito, Ecuador and taking the 500 mile flight

off the South American coast to the archipelago, we boarded a cruise ship on Isla

Baltra and sailed off. However, this was not your typical cruise; we

visited many different islands and disembarked on two strenuous excursions per day.

The most striking thing I noticed from the very beginning was the lack of civilization. The Galápagos is an untamed wilderness, with only a handful of human establishments on a few islands. From observation, the environment looked as if it had not changed in a thousand years. But I know for a fact that the Galápagos is far from a static environment. The very landscape is changing, as it is a chain of islands formed from active volcanos. One of the first excursions we made was on a lava field on Isla Santiago. We rode a dinghy from the ship to the coast of the island. A plain of dried lava stretched as far as the eye could see, straight from the ocean up to the base of a recently active volcano that last erupted in the late 19th Century. For such a seemingly inhospitable environment, the island was teeming with life. Thousands of Sally Lightfoot crabs and marine iguanas sat on the barren terrain, basking in the sun and gazing at us with uncertainty.

This was not the last time I saw these creatures, however. We had a half-dozen more islands to visit. At Isla Isabela, we had the opportunity to snorkel with the iguanas, Galápagos penguins, and sea lions. Many of these animals had never even interacted with humans. On Isla Santa Cruz, I saw all the unique vegetation zones characteristic of the Islands. As we hiked upward in elevation, we watched the landscape transition from rocky coastline to the arid zone, a desert-like area of small shrubs, cacti, and many of Darwin's famed finches. The higher we went upward, the more trees appeared, until finally we reached the Scalesia zone, a dense, otherworldly cloud forest. The pinnacle of my journey, however, was visiting El Chato Tortoise Reserve, the home to many of the remaining Galápagos tortoises on the archipelago.

Unfortunately, all good things come to an end, my cruise being one of them. I had to make my way back to the United States. For certain, I can say that I have never learned so much about the natural world on a vacation. This small group of islands will in my mind always hold the award for the most beautiful section of land on the planet. The delineation of each community in the Galápagos is distinct, but all organisms in each have adaptations that have allowed them to survive amongst the plethora of environmental factors the Islands present. Darwin could not have found a more suitable place to carry out his research.

The most striking thing I noticed from the very beginning was the lack of civilization. The Galápagos is an untamed wilderness, with only a handful of human establishments on a few islands. From observation, the environment looked as if it had not changed in a thousand years. But I know for a fact that the Galápagos is far from a static environment. The very landscape is changing, as it is a chain of islands formed from active volcanos. One of the first excursions we made was on a lava field on Isla Santiago. We rode a dinghy from the ship to the coast of the island. A plain of dried lava stretched as far as the eye could see, straight from the ocean up to the base of a recently active volcano that last erupted in the late 19th Century. For such a seemingly inhospitable environment, the island was teeming with life. Thousands of Sally Lightfoot crabs and marine iguanas sat on the barren terrain, basking in the sun and gazing at us with uncertainty.

This was not the last time I saw these creatures, however. We had a half-dozen more islands to visit. At Isla Isabela, we had the opportunity to snorkel with the iguanas, Galápagos penguins, and sea lions. Many of these animals had never even interacted with humans. On Isla Santa Cruz, I saw all the unique vegetation zones characteristic of the Islands. As we hiked upward in elevation, we watched the landscape transition from rocky coastline to the arid zone, a desert-like area of small shrubs, cacti, and many of Darwin's famed finches. The higher we went upward, the more trees appeared, until finally we reached the Scalesia zone, a dense, otherworldly cloud forest. The pinnacle of my journey, however, was visiting El Chato Tortoise Reserve, the home to many of the remaining Galápagos tortoises on the archipelago.

Unfortunately, all good things come to an end, my cruise being one of them. I had to make my way back to the United States. For certain, I can say that I have never learned so much about the natural world on a vacation. This small group of islands will in my mind always hold the award for the most beautiful section of land on the planet. The delineation of each community in the Galápagos is distinct, but all organisms in each have adaptations that have allowed them to survive amongst the plethora of environmental factors the Islands present. Darwin could not have found a more suitable place to carry out his research.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)